This perspective paper draws upon the constitutional provisions concerning the rights of nature in Ecuador and Bolivia to offer nuanced recommendations for integrating the rights of nature into Ghana’s environmental governance legal framework. It characterizes the rights of nature as a transformative, 21st-century legal revolutionary approach within global legal environmental frameworks. The paper emphasizes the importance of adopting an integrated rights of nature paradigm that recognizes not only human rights but also the intrinsic rights of nature within economic and legal systems. Furthermore, it highlights the limitations of Ghana’s current constitutional framework, which predominantly emphasizes human rights in environmental governance, and advocates for the recognition of the rights of nature as an effective legal mechanism to address the nation’s ongoing environmental crises. The paper proposes specific constitutional provisions in Ghana that could serve as strategic entry points for mainstreaming the rights of nature, along with well-founded suggestions for their incorporation and reformulation. Ultimately, the paper argues that the integration of the rights of nature into Ghana’s constitution would foster a more holistic, morally equitable, inclusive, ethically considerate, and sustainable environmental legal framework. Such a reform would position Ghana alongside other nations committed to ecological justice and the protection of all living beings—human and non-human—promoting a mutually interdependent and harmonious relationship within ecosystems.

Introduction: The state of Ghana’s natural elements and environment

“To turn nature from declining to thriving, we need fundamental changes to how nature is recognized in our political decisions. We need a Right to Nature and nature needs a right to exist.”

– Adrian Bebb, Friends of the Earth-Europe

Ghana, like many developing nations, is confronting a profound environmental crisis with far-reaching implications for public health, socio-economic stability, and cultural integrity. This ecological crisis, characterized by widespread environmental degradation, demands urgent and decisive intervention; otherwise, the country risks irreversible ecological collapse. Numerous scholars and environmental organizations have issued stark warnings about Ghana’s impending ecocide if current destructive practices persist beyond 2030. Amid rapid population growth, urbanization, industrialization, and expanding agricultural sectors, one of the most notorious drivers of environmental harm is the phenomenon locally known as “Galamsey.” Originally referring to traditional small-scale mining involving simple tools, the term has evolved to denote large-scale, often illegal, extractivist practices employing sophisticated machinery—such as bulldozers, excavators, and water pumps—often operating without regard for ethical or environmental standards. This shift has precipitated catastrophic damage to Ghana’s water bodies, land, and ecosystems, with levels of turbidity in rivers soaring far beyond safe thresholds; for instance, turbidity readings have exceeded 14,000 NTU—over 120% of the Ghana Water Company’s processing capacity—rendering water unsafe for human consumption (Charity WaterAid, 2024). If decisive measures are not implemented to curb these destructive practices, Ghana faces the alarming prospect of becoming increasingly dependent on water imports, further threatening its ecological integrity and public health (Ghana Water Company, 2024). This pressing crisis underscores the urgent need to re-evaluate and reform Ghana’s environmental governance, including the potential integration of innovative legal frameworks such as the rights of nature.

Limitations of Ghana’s Environmental Governance Legal Framework: The Rights of Nature

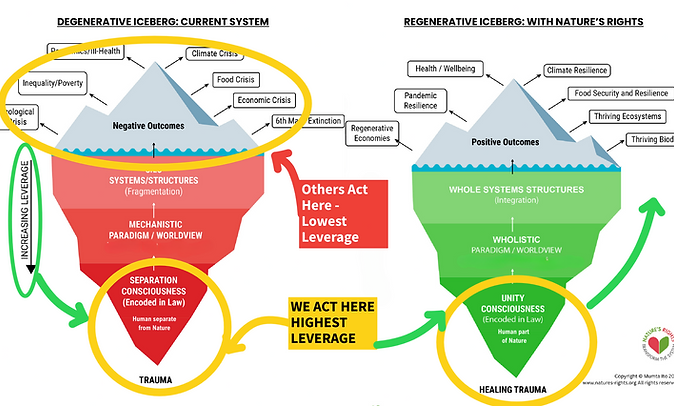

Regrettably, Ghana’s existing legal architecture for environmental governance—and its highest legal instrument—primarily emphasizes human rights to access and utilize natural resources, rather than recognizing the intrinsic rights of nature itself. Ghana’s legal frameworks lack explicit acknowledgment of the Rights of Nature, instead focusing predominantly on regulatory measures, permits, and enforcement mechanisms that treat nature as a resource subordinate to economic and developmental interests (Adom, 2025). This anthropocentric approach perpetuates a fragmented worldview that segregates human, environmental, and economic spheres, thereby failing to adopt a holistic perspective that recognizes nature’s inherent value and rights. Consequently, Ghana’s environmental laws tend to address superficial symptoms of ecological degradation without tackling the underlying causes rooted in the exploitative and anthropocentric paradigm that views nature solely as a resource for human benefit.

The concept of Rights of Nature (RoN) offers a transformative alternative—an indigenous and global movement advocating for the recognition of the foundational rights of natural entities such as rivers, mountains, ecosystems, and entire biomes to exist, regenerate, thrive, and perform their ecological functions (Margil, 2024). RoN challenges traditional legal paradigms by asserting that nature is not merely property to be exploited but a living entity with intrinsic rights, deserving of legal protection and moral consideration (Alves et al., 2023). Globally, frameworks such as those established in Ecuador, Bolivia, and New Zealand demonstrate how integrating the Rights of Nature into legal and constitutional systems can foster a more sustainable and respectful relationship between humans and the environment (Borrows, 2010; Charpleix, 2018; Kimmerer, 2013).

The movement emphasizes that recognizing nature’s rights can catalyze robust legal protections, promote ecological resilience, and encourage sustainable practices that prioritize the health of ecosystems. Such recognition aligns with broader biocentric philosophies that view the environment as a stakeholder in governance, rather than a passive resource to be exploited. Incorporating indigenous cosmologies and traditional ecological knowledge further enriches this approach, emphasizing relationship, reciprocity, and collective responsibility—principles often marginalized within Western legal paradigms but essential for fostering harmonious coexistence with nature (Pelizzon, 2025; Ruru, 2018).

In jurisdictions like Bolivia, Ecuador, and New Zealand, indigenous perspectives have informed legal reforms that extend rights beyond human persons to rivers, forests, and ecosystems—affirming their status as living entities with rights to flourish and regenerate (Kimmerer, 2013). These models demonstrate that recognizing the intrinsic value and rights of nature can lead to more sustainable and equitable environmental stewardship, conserving biodiversity, and safeguarding community health.

For Ghana, embracing the Rights of Nature presents a vital opportunity to rectify the limitations of its current legal approach, fostering a paradigm shift toward environmental justice rooted in ethical, cultural, and ecological principles. Such reform could help transcend the narrow, resource-centric view that underpins current laws and instead promote a resilient, inclusive, and sustainable relationship with the natural environment—one that respects nature’s inherent rights and recognizes its critical role in human well-being.

Lessons for Ghana on Incorporating the Rights of Nature into National Constitution and Law: Insights from Ecuador and Bolivia

Ecuador and Bolivia stand out as pioneering examples of integrating the Rights of Nature into their constitutional frameworks, offering valuable lessons for Ghana’s pursuit of environmental justice and sustainable development. Ecuador’s groundbreaking move in 2008 marked the first national constitutional recognition of nature’s rights, positioning Pacha Mama—Mother Earth—as a legal entity endowed with inherent rights to exist, persist, and regenerate. This constitutional innovation was deeply rooted in indigenous Andean cosmologies, particularly among the Quechua communities, and was inspired by broader global movements, notably the 2006 recognition of Rights of Nature in the United States. The Ecuadorian Constitution’s Chapter 7, titled “Rights for Nature,” enshrines rights such as the right to existence, restoration, and the protection against severe environmental harm, explicitly empowering individuals and communities to demand legal recognition and enforcement of these rights (Chapron et al., 2019; Kauffman & Martin, 2018). Articles 71 through 74 establish a comprehensive legal framework that emphasizes ecological balance, the right to restore damaged ecosystems, and the sustainable utilization of natural resources—aimed at addressing the root causes of environmental degradation, especially in the context of mining conflicts and resource exploitation.

Similarly, Bolivia’s constitutional law, enacted in 2012, reflects a profound indigenous worldview centered on “Pachamama” (Mother Earth) and the philosophy of “Vivir Bien” (Living Well). This framework legally recognizes nature as a subject with rights to life, biodiversity, water, and a pollution-free environment, rooted in principles of harmony, collective good, and ecological balance (Acosta, 2013). The Bolivian law delineates clear obligations for the state and society to uphold these rights, including the development of proactive policies, community participation, and the establishment of institutional mechanisms such as the Office of the Mother Earth to oversee compliance and enforcement (Asamblea Legislativa Plurinacional de Bolivia, 2010). These legal innovations have not only influenced national policy but also contributed significantly to global discussions on Earth jurisprudence, culminating in the 2010 Universal Declaration of the Rights of Mother Earth.

The Ecuadorian and Bolivian experiences underscore several vital lessons for Ghana. The stark environmental challenges Ghana faces—particularly the destructive practices of extractivism, illegal mining, and ecosystem degradation—necessitate a paradigm shift in legal frameworks. Recognizing the intrinsic rights of nature within Ghana’s constitution could serve as a transformative step toward environmental justice, aligning legal principles with indigenous ecological knowledge that has historically promoted harmony with nature. Indigenous communities in Ghana have long upheld norms, taboos, and cosmologies that emphasize the sanctity of rivers, forests, and biodiversity, reflecting an ecocentric worldview that values the interconnectedness of all living beings (Adom, 2018). Embedding the Rights of Nature into Ghana’s natural resource governance legislation would elevate these indigenous insights, challenging the prevailing anthropocentric paradigm that treats ecosystems solely as commodities for human exploitation.

By adopting a constitutional recognition of nature’s rights, Ghana can establish a robust legal precedent that emphasizes ecological integrity, cultural respect, and sustainable development. Such a framework would not only empower local communities to advocate for environmental preservation but also foster a more holistic conception of justice—one that recognizes the environment as a stakeholder with inherent rights. Ultimately, the Ecuadorian and Bolivian models highlight the potential for legal reform to catalyze a profound cultural and ecological shift, steering Ghana toward a future where human well-being is harmoniously aligned with the health of the natural world.

Ghana’s Constitution and the Path Forward for Recognizing the Rights of Nature

While Ghana’s 1992 Constitution robustly safeguards fundamental human rights and freedoms, it conspicuously lacks explicit acknowledgment of the rights of the natural environment. This omission poses significant limitations, especially as Ghana grapples with escalating environmental crises—including widespread deforestation, pollution, climate change impacts, and biodiversity loss—threatening both ecological integrity and human well-being. Recognizing the intrinsic rights of nature is not merely a legal reform; it is an imperative for fostering a culture of ecological stewardship, empowering civil society, and enabling local communities to participate actively in environmental governance.

Fortunately, Ghana’s constitutional framework contains provisions that can serve as strategic entry points for mainstreaming the Rights of Nature. By reformulating and expanding these provisions, Ghana can align its legal system with emerging global paradigms that recognize nature as a rights-bearing entity.

Reforming Article 13: Recognizing the Rights of Natural Elements

Currently, Article 13 under Chapter Five on Fundamental Human Rights and Freedoms provides for the right to life. This provision can be expanded to explicitly include the rights of natural elements—such as rivers, forests, and other ecosystems—that are essential to community health and sustenance. A proposed reform could state:

“Recognize the rights of natural elements within protected and community lands, including rivers, forests, and ecosystems, to exist, thrive, and regenerate, thereby ensuring the ecological services vital for the health and well-being of local communities.”

This reform underscores the importance of safeguarding ecological functions from destructive practices like illegal mining (galamsey) and environmentally harmful legal mining activities, emphasizing that natural elements possess inherent rights to perform their ecological roles without undue interference.

Leveraging Chapter 21: Protecting Lands and Natural Resources

Ghana’s Chapter 21, which addresses land and natural resources, presents another crucial avenue. A reformulation of Article 268 could stipulate that Parliament ratifies the recognition of personhood rights for specific natural elements, especially water bodies and forests under threat from unsustainable extractive activities. This approach aligns with the principles of ecocide law, aiming to criminalize environmentally destructive practices that threaten ecosystems and, by extension, human health. Proposed provisions include:

- Parliament, by resolution, should ratify the recognition of legal personhood for natural elements—such as rivers, lakes, and forests—to protect them from illegal and environmentally destructive practices like galamsey and unregulated mining.

- Apply principles from ecocide law to criminalize actions that cause severe harm to nature, recognizing such acts as offenses that threaten both ecological integrity and human survival.

Reformulating Article 26: Protecting Indigenous Cultural Practices and Sacred Spaces

Ghana’s cultural rights provisions, particularly Article 26, can be adapted to reinforce indigenous communities’ rights to preserve sacred natural sites and traditional ecological knowledge. This recognizes that indigenous cosmologies often uphold a harmonious relationship with nature, emphasizing respect, reciprocity, and the sacredness of specific natural spaces. A suggested reform could state:

“Communities shall have the right to engage in and preserve indigenous cultural practices that uphold the interdependence and harmony between humans and nature, including the protection of designated sacred natural sites essential to their cultural and spiritual identity.”

This provision would help prevent encroachment and exploitation of culturally significant spaces while safeguarding indigenous knowledge systems that promote ecological sustainability.

The Way Forward: Embracing an Integrated Nature’s Rights Framework

The recognition of the rights of nature in Ghana’s constitution aligns with a growing global discourse that underscores the interconnectedness of human well-being and ecological health. The Integrated Rights Framework (Figure 1) developed by Mumta Ito advocates for harmonizing human, ecological, and economic rights—recognizing that the health of ecosystems is fundamental to sustainable development. The framework advocate for the implementation of the science of interconnection of nature, people and the economy (Figure 2). This paradigm shift challenges the mechanistic, 17th-century legal paradigms still prevalent in Ghana that treat nature, humans, and the economy as separate entities. Instead, it promotes a model where nature’s rights are integrated into national law, fostering equity, resilience, and ecological integrity.

Implementing this framework requires clear legal definitions, specific mechanisms for enforcement, and public capacity-building. Initially, a pragmatic approach could focus on recognizing the rights of key natural elements—such as Ghana’s iconic rivers, forests, and endangered ecosystems—serving as catalysts for broader legal and societal acceptance. Over time, this incremental strategy can build momentum toward comprehensive constitutional reform, embedding the Rights of Nature as a fundamental principle of Ghana’s environmental governance. Ghana’s path forward entails bold constitutional reforms that recognize the intrinsic rights of nature, informed by successful models in Ecuador and Bolivia. Such reforms would not only fortify ecological protection but also catalyze a cultural shift toward a more sustainable, respectful, and harmonious relationship between humans and the natural world—ensuring the health of Ghana’s environment for generations to come.

Conclusion

This perspective paper underscores the imperative of integrating the rights of nature into Ghana’s constitutional reforms, drawing lessons from the cases of Ecuador and Bolivia. The study argues that recognizing the intrinsic value of nature within Ghana’s constitution—alongside existing human rights—would foster a more comprehensive, morally equitable, inclusive, and sustainable environmental legal framework. Such an approach would advance ecological justice by affirming the fundamental rights of all living beings—both human and non-human—and promote a culture of stewardship and sustainability. This would particularly benefit marginalized local communities and environmental advocates, empowering them to litigate and advocate for the protection of their ecosystems against ecological degradation. Moreover, embedding the rights of nature would align Ghana with international best practices, reaffirming its commitments to global environmental agreements such as the Convention on Biological Diversity and the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals. While the prospects for mainstreaming the rights of nature into Ghana’s constitution are promising and potentially transformative, careful, context-sensitive legal drafting is essential—one that incorporates local traditions and ecological realities. As demonstrated through the examples of Ecuador and Bolivia, a nuanced approach—grounded in these successful models—can effectively promote ecological justice alongside human rights, ensuring a more resilient and equitable environmental governance framework for Ghana.

“It’s irrational to have societal systems that undermine Nature. The rights based approach is a very practical way to achieve systemic change.Establishing a new set of rights for Nature is something that can really deliver the change that we so desperately and urgently need.”

– Cillian Lohan, European Economic and Social Committee

Funding: This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest: The author declares no conflict of interest.

Author Bio note

Dickson Adom is a pluridisciplinary researcher whose work focuses on using indigenous knowledge systems for developing innovative strategies, pedagogies and community-led projects aimed at conserving nature, preserving cultural heritage and building resilient local communities. He is a Senior Member in the Department of Educational Innovations in Science and Technology, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Ghana. He is the lead campaigner for the Rights of Nature Ghana (RoNAG) Movement, a team of dedicated environmental enthusiasts who are passionate and poised to assume the role of spokespersons in defending the rights of nature in Ghana.

References

Acosta, A. (2013, January 1). Extractivism and Neoextractivism: Two sides of the same curse. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/293103296_Extractivism_and_Neoextractivism_Two_sides_of_the_same_curse

Adom, D. (2025). Stop the Impending Ecocide against Nature: Revisiting Ghanaian Indigenous Sensibilities and Setting the Tone for a Rights of Nature Ghana (RoNAG) Movement. U.S.A.: Centre for Democratic and Environmental Rights, URL: https://www.centerforenvironmentrights.org/news/guest-essay-the-rights-of-nature-ghana-movement

Adom, D. (2018). Traditional Cosmology and Nature Conservation at the Bomfobiri Wildlife Sanctuary of Ghana.’ Nature Conservation Research, 3(1): 35-57.

Alves, F., Costa, P. M., Novelli, L., & Vidal, D. G. (2023). The rights of nature and the human right to nature: An overview of the European legal system and challenges for the ecological transition. Frontiers in Environmental Science, 11: 1175143. https://doi.org/10.3389/fenvs.2023.1175143

Borrows, J. (2010). Canada’s indigenous constitution. University of Toronto Press.

Carducci, M., Bagni, S., Lorubbio, V., Musarò, E., Montini, M., Barreca, A., Maesa, C., Ito, M., Spinks, L., & Powlesland, P.(2020). Towards an EU Charter of the Fundamental Rights of Nature. Brussels: The European Economic and Social Committee (EESC)

Chapron, G., Epstein, Y., & López-Bao, J. V. (2019). A rights revolution for nature. Science, 363(6434): 1392–1393. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aav5601

Charpleix, L. (2018). The Whanganui River as Te Awa Tupua: Place-based law in a legally pluralistic society. The Geographical Journal, 184(1): 19–30. https://doi.org/10.1111/geoj.12238

Gutmann, A. (27 January 2025). Rights of Nature in Ecuador. https://www.boell.de/en/2025/01/27/rights-nature-ecuador

Kauffman, C. M., & Martin, P. L. (2018). Constructing Rights of Nature Norms in the US, Ecuador, and New Zealand. Global Environmental Politics, 18(4): 43–62. https://doi.org/10.1162/glep_a_00481

Kimmerer, R. W. (2013). Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge and the Teachings of Plants (1st ed.). Milkweed Editions.

Pelizzon, A. (2025). Rights of Nature. In: Ecological Jurisprudence. Contemporary Environmental Law and Policy. Singapore: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-96-0173-8_6

WaterAid Ghana (September 13, 2024). WaterAid demands immediate halt to illegal mining as water supply drops 75% due to pollution. https://www.wateraid.org/gh/blog/wateraid-demands-immediate-halt-to-illegal-mining-as-water-supply-drops-75-due-to-pollution

Ghana Water Company (October 22, 2024). Ghana’s Path to Sustainable Water Supply:

Reforming Rural and Small-Town Water Management for SDG 6

https://www.wateraid.org/gh/blog/ghanas-path-to-sustainable-water-supply-reforming-rural-and-small-town-water-management-for

Ruru, J. (2018). Listening to Papatūānuku: a call to reform water law. Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand, 48(2–3): 215–224. https://doi.org/10.1080/03036758.2018.1442358

Dickson Adom

1Senior Member, Department of Educational Innovations in Science & Technology

Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Ghana

2Research Fellow, INTI International University, Malaysia

3Lead Campaigner, Rights of Nature Ghana Movement (RoNAG)

4Advisor, Gower Street-UK

- mail: adom@knust.edu.gh

Orcid: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0559-4173